Henry Clay's Visit to Richmond

The fact that Richmond was one of the earliest settled communities in Indiana, was on the National Road, and on the only railroad that connected Indianapolis with the East, together with the character of her citizens, made her the center of many stirring political events in the early days. Politics in this locality were always, as they are now, very exciting. The Friends, who had a liberal settlement here, were important factors, and their vote was courted. The county, in its early history, was strongly Whig. When the slavery question came to the front, however, there was a division of sentiment in the county and party lines were broken by a great many, and the fight between the Abolitionists and Whigs became extremely bitter and personal. So intense was the feeling among the Friends that their church was split into two factions. What is now Fountain City, then Newport, was the center of the Abolition element of Wayne county and was a central station on the Underground Railway.

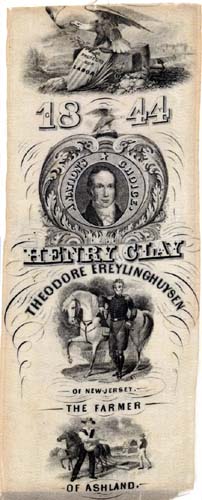

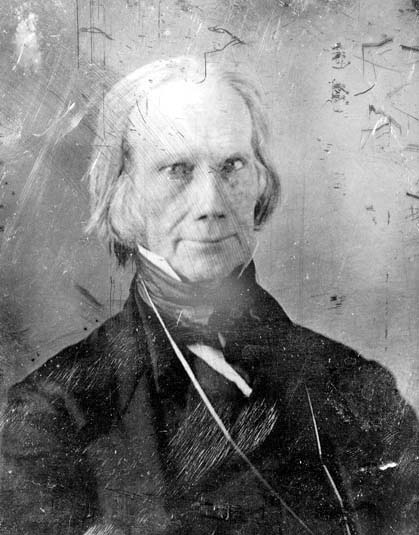

The most exciting incident of the antebellum days in this vicinity occurred in the fall of 1844 (sic.; should be 1842). It was on the first Saturday in October, 1844 (sic.), that Henry Clay, the candidate for President on the Whig ticket, arrived in Richmond on his way from Dayton, Ohio, to Indianapolis, he then being on a speech making tour in his own behalf. While here he was the guest of Elijah Coffin and Stephen B. Stanton. His appearance here was known ahead of time and the town was the scene of a wonderful multitude of people, greater than ever before in its history. The Abolitionists had determined to petition him for an interview relative to the freeing of his slaves. A petition with over 2,000 names had been prepared and had been signed by the committee having it in charge – Daniel Worth, Peter Croker, Hiram Mendenhall, and Samuel Mitchell. They had come to Richmond for that purpose, and it was known to the Whigs. Excitement ran high and threats of violence were made against any man who would insult Henry Clay by offering him such a petition, for so the Whigs called the action. The privilege to privately present their petition was denied the Abolitionists, it not being supposed that they would have the courage to do it openly. The speaking occurred from a temporary platform, erected where the properties of Doctors Hibberd and Weist later stood, on North Eighth street, between A and B. James Rariden presided and, upon the meeting being called to order, asked that anyone having petitions to present to Mr. Clay would please bring them forward. This was done to force the Abolitionists to either back down or else incur the anger of the hostile crowd of bitter partisans. In this announcement it was also made known that any petition would be replied to by Mr. Clay at that time. When this announcement was made the Abolitionists, through Hiram Mendenhall, a fearless and stalwart farmer, sent their petition to the stand. When he started with it, cries of “Mob him!” “Stab him!” “Kill him!” arose from the crowd, the vast majority of whom were Clay partisans. Seeing the seriousness of the occasion, Clay stepped to the edge of the platform and importuned the crowd not to resort to violence. It is said that only his plea saved Mendenhall’s life. The petition was handed to Rariden (Clay refusing to touch it) and was read by him. Then Clay made answer. For over an hour he poured down upon the heads of the Abolitionists in general and the petitioners in particular a storm of eloquent sarcasm, ridicule, and argument, such as was probably never heard in Richmond before or since, because it was only such as Henry Clay could give. He even became abusive, and finished by telling the petitioners to “Go home, go home, and mind your own business.”

Of course the speech was a strong one in the eyes of the crowd, but it is said that this very same Richmond speech defeated Clay and elected Polk. As fast as the mails would carry the news of the meeting it was sent to the Abolitionists of New York, where the speech was taken as a text and stirred the friends of Abolition of that State to such activity that it went against Clay. It was a pivotal State and decided the day. After Clay’s defeat the Abolition press, remembering his closing words to Wayne county Abolitionists, said gleefully: “We are at home, Mr. Clay.”

From Fox, H. C. Memoirs of Wayne County and the City of Richmond Indiana, Volume I. Madison, Wis.: Western Historical Assn., 1912: 495-497.